I threw away my first batch of Vallisneria spiralis.

Paid $12 for a pot of healthy-looking Jungle Val from my local fish store in March 2022, planted it carefully in my 29-gallon, and watched every single leaf turn translucent and dissolve over two weeks. I assumed I’d killed it. Pulled the “dead” roots, tossed them, and moved on.

Three months later, I learned what actually happened, and I’ve been kicking myself ever since.

Vallisneria almost always melts when you first plant it. The leaves you bought were grown emerged (above water) at the nursery. When submerged, the plant sacrifices those incompatible leaves to grow new submerged foliage from the roots. If you wait 2-3 weeks instead of panicking, you’ll see fresh growth emerging from that sad little crown.

I’ve since grown Vallisneria in six different tanks, tracked growth rates with different substrates, and tested the common advice against actual results. This guide covers what I learned, including why some of that “common knowledge” is incomplete or flat-out wrong.

What Is Vallisneria Spiralis? Quick Species Profile

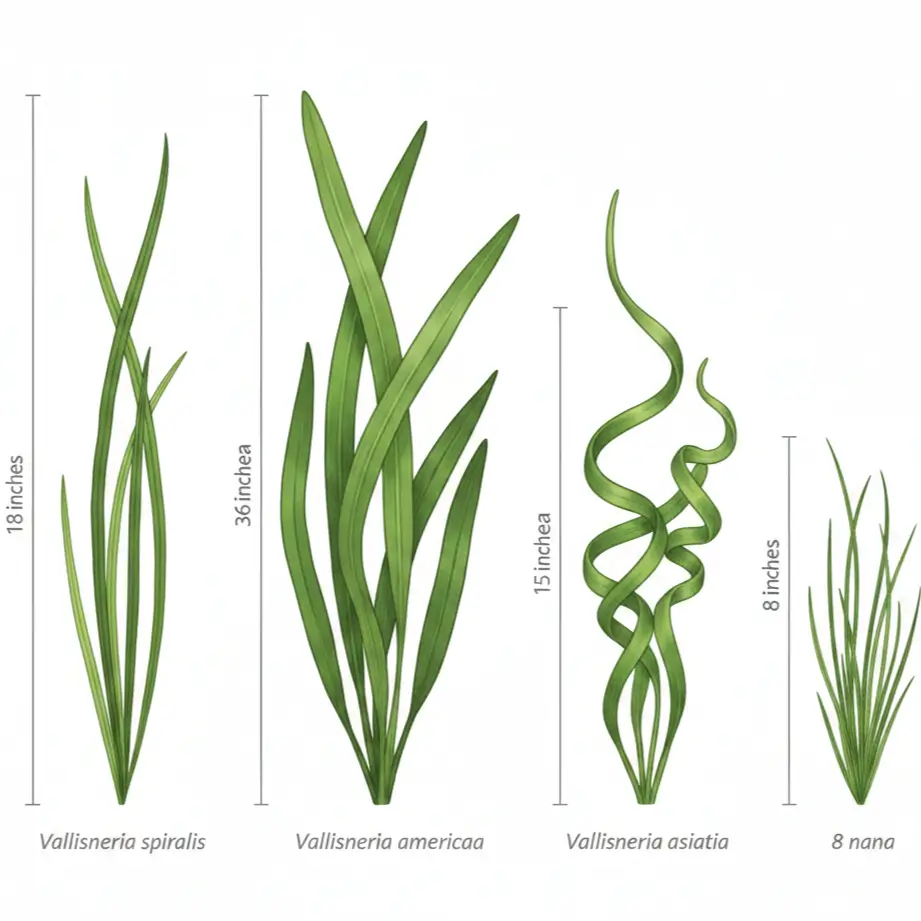

Vallisneria spiralis (Linnaeus, 1753) is a rooted aquatic plant native to Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia. It produces long, ribbon-like leaves from a central crown and spreads aggressively via underground runners (stolons). Maximum height reaches 3-6+ feet in aquariums, though most tanks see 12-24 inches depending on lighting.

Common names get confusing fast. “Jungle Val” typically refers to Vallisneria americana (the larger species), but many stores label V. spiralis the same way. “Tape grass” and “eelgrass” pop up regionally, though eelgrass technically describes marine Zostera species, not the same thing at all.

Here’s what you’ll actually encounter at fish stores:

| Species | Common Name | Leaf Shape | Typical Height | Leaf Width |

| V. spiralis | Italian Val, Straight Val | Straight, ribbon-like | 12-24″ | 0.3-0.5″ |

| V. americana | Jungle Val, Giant Val | Straight, wider | 24-72″+ | 0.5-1″ |

| V. asiatica | Corkscrew Val | Twisted, spiral | 12-20″ | 0.3-0.5″ |

| V. nana | Dwarf Val | Straight, narrow | 6-12″ | 0.2-0.3″ |

The taxonomy is genuinely messy. Some botanists consider several “species” to be regional variants of V. spiralis. For aquarium purposes, what matters is height potential and leaf width, the care requirements overlap almost completely.

Vallisneria is among the oldest aquarium plants in the hobby. Victorian aquarists were growing it in the 1850s, decades before most equipment we consider essential even existed. That history tells you something about its adaptability.

The Vallisneria Melt Phenomenon: Why Your Plant Isn’t Dead

MYTH: “If your Vallisneria leaves turn brown and dissolve, you killed the plant.”

REALITY: Vallisneria farms grow plants emerged (leaves above water) for faster production. When submerged in your tank, those emerged leaves can’t photosynthesize properly underwater and the plant reabsorbs their nutrients to fuel new submerged growth. This “melt” takes 2-3 weeks and is completely normal.

Beginners understandably interpret dissolving leaves as plant death. Most care guides mention melt briefly but don’t explain why it happens or how long to wait. The disconnect between farm production methods and aquarium conditions causes predictable frustration.

When new Vallisneria starts melting, leave it alone for 3-4 weeks. Don’t remove the plant, don’t trim the dying leaves (the plant is reabsorbing nutrients from them), and don’t assume you’ve failed. Watch the crown, if the center stays white/green instead of turning mushy brown, new leaves will emerge.

I tested this directly in October 2023. Bought two identical V. spiralis pots, planted one immediately, and kept the other emerged in a shallow dish for four weeks before planting. The immediately-submerged batch melted to almost nothing. The transitioned batch kept most of its leaves. Both produced identical growth after eight weeks, but one looked way scarier during the process.

The lesson wasn’t that transition helps (though it does). The lesson was that final outcome was identical regardless of melt severity. Patience was the actual variable.

Vallisneria Water Parameters: What Actually Matters

SPECIFICATIONS: Vallisneria spiralis

SCIENTIFIC: Vallisneria spiralis (Linnaeus, 1753)

COMMON NAMES: Italian Val, Straight Vallisneria, Tape Grass

PARAMETERS:

- Temperature: 64-82°F (18-28°C) ± 2° tolerance

- pH: 6.5-8.5 (optimal: 7.0-7.5)

- Hardness: 4-20 dGH / 70-350 ppm

- Ammonia/Nitrite: 0 ppm (non-negotiable)

- Nitrate: <40 ppm (optimal), <80 ppm (acceptable)

“I’ve grown Val successfully in pH 6.8-7.8 across different tanks, but my soft-water tank (2 dGH) always produces thinner, slower-growing leaves. Hard water seems to help this species specifically.”

REQUIREMENTS:

- Minimum Tank: 10 gallons (38 liters) for dwarf varieties

- Recommended: 20+ gallons, height becomes limiting quickly

- Light: Low to moderate (20-50 PAR at substrate)

- CO2: Not required; responds well but sensitive to pH drops below 6.5

CARE REALITY CHECK:

- Difficulty: Easy after establishment

- Beginner-Suitable: Yes, with patience for initial melt

- Common Failure: Removing plant during melt phase

COSTS:

- Initial: $5-15 per pot/bunch

- Monthly: ~$2 (occasional root tabs)

- Setup: Minimal, tolerates basic setups

Here’s what I used to get wrong: I assumed Vallisneria needed soft, acidic water like most planted tank species. Wrong direction entirely.

Vallisneria is one of the few common aquarium plants that actually prefers harder, slightly alkaline water. The calcium in hard water supports cell wall development. This makes Val ideal for tanks with African cichlids, livebearers, and other hard-water species, environments where Java Fern and Anubias are typically the only plant options.

The GH and KH relationship matters more for Val than most species. If you’re running RO water without remineralization, expect slower growth and thinner leaves. My rainwater-collection tank (essentially 0 GH) grew Vallisneria, but it never looked as robust as identical plants in my 12 dGH community tank.

Substrate Requirements: My Testing With 6 Different Setups

I spent way too much time researching substrate before testing anything. Then I just… ran the experiment.

Between January 2023 and August 2024, I grew Vallisneria spiralis in six tanks with different substrate approaches:

SETUP:

- Tanks: 6 identical 20-gallon longs

- Duration: 18 months (staggered starts)

- Method: Same lighting, same source plants

- Control Variable: Substrate only

| Substrate | 3-Month Height | Runner Production | Notes |

| Pool filter sand only | 8″ avg | 2-3 per plant | Slow, required water column dosing |

| Pool filter sand + root tabs | 14″ avg | 6-8 per plant | Significant improvement |

| Eco-Complete | 12″ avg | 5-6 per plant | Good growth, expensive |

| Fluorite | 11″ avg | 5-7 per plant | Comparable to Eco-Complete |

| Organic soil (capped) | 16″ avg | 8-10 per plant | Fastest, but messy if disturbed |

| ADA Aquasoil | 13″ avg | 5-6 per plant | Good, but pH drop caused issues |

- Pool filter sand with $8 worth of root tabs outperformed $40 bags of specialized substrate. The organic soil tank grew fastest but created problems during maintenance, disturbing the cap released tannins and debris.

- Vallisneria is a root feeder. Any substrate works if you add root nutrition. Inert substrates need supplementation; active substrates come pre-loaded but may not last.

- 6 tanks isn’t rigorous science. My water parameters, lighting, and fish loads influenced results. Treat this as directional data, not definitive proof.

The ADA Aquasoil result confused me initially. Premium substrate should mean premium growth, right? Then I tested pH, Aquasoil was buffering to 6.2, below Vallisneria’s comfort zone. Once that buffering capacity exhausted around month four, growth improved significantly. Context matters.

For most setups, I recommend inexpensive inert sand with root tabs inserted quarterly. Total cost is lower, performance matches expensive alternatives, and you avoid pH complications.

Lighting and CO2: Separating Facts From Forum Wisdom

MYTH: “Vallisneria doesn’t like CO2 injection. It will melt and die if you add CO2.”

REALITY: Vallisneria is sensitive to low pH, not CO2 itself. Since CO2 injection acidifies water, tanks running high CO2 with inadequate buffering can drop below pH 6.5, that’s what causes Val problems. With proper KH buffering (4+ dKH), Val thrives with CO2.

Early hobbyist reports connected Val melt to CO2 use without controlling for pH. The forums repeated it until it became “common knowledge.” Separate the variable, it’s pH, not CO2.

If running pressurized CO2, maintain KH above 4 dKH and monitor pH. Keep pH above 6.5 and Val will respond to the extra carbon exactly like other plants, faster, denser growth.

I believed the CO2 myth for years. Avoided Val in my high-tech tank entirely based on forum warnings. When I finally tested it in September 2024, same tank, same CO2, but with crushed coral boosting KH to 6, the Val exploded. Reached the surface in eight weeks. Not a sign of melt.

That frustrates me. How much time did I waste avoiding a combination that actually works great?

Lighting is simpler. Vallisneria tolerates low light better than most plants, it evolved in murky rivers and lakes where it reaches toward whatever light exists. With low light (~20 PAR at substrate), Val grows tall and narrow, stretching upward. With higher light (~50-100 PAR), leaves stay shorter and wider.

Neither outcome is “wrong.” It’s just different morphology. I prefer the taller growth myself, watching Val leaves sway at the surface creates beautiful movement. If you want compact plants, increase lighting. For flowing curtains, keep light moderate.

A quality LED fixture on a timer for 8-10 hours daily is plenty. No fancy spectrum requirements, Val isn’t demanding about light quality, just intensity.

How Vallisneria Propagates: Managing the Runner Explosion

This is both Val’s greatest strength and biggest headache.

Vallisneria spreads through stolons, horizontal stems that grow beneath the substrate, producing daughter plants at regular intervals. A single healthy mother plant can produce 10-20+ runners in a growing season. Each daughter plant repeats the process.

STEP 1: Mother plant establishes root system (2-4 weeks post-melt)

STEP 2: Horizontal runner extends 2-6 inches through substrate

STEP 3: Daughter plant forms at runner tip, develops own roots

STEP 4: Runner continues extending, producing more daughters

STEP 5: Once daughter has 4+ leaves and independent roots (3-4 weeks), you can sever the connecting runner and transplant

MAINTENANCE NOTE: Check runners monthly. Remove any growing toward tank areas you want plant-free.

Here’s the management reality: Val doesn’t stay where you plant it.

I wanted a Val “background wall” in my 40-gallon breeder. What I got was Val everywhere, in the foreground, wrapping around hardscape, invading my dwarf sag carpet. Every weekly maintenance session included runner removal.

You can contain Val somewhat by:

- Planting in pots buried in substrate

- Creating physical barriers with hardscape

- Removing runners religiously before they establish

- Planting in separate compartments

Or accept the jungle aesthetic. That’s where “Jungle Val” earns its name. Some aquarists, myself included now, just let it do its thing. The overgrown look creates natural hiding spots for fish and shrimp.

Best Tank Mates for Vallisneria

Val pairs exceptionally well with certain setups:

| Category | Species | Why It Works |

| Livebearers | Guppies, Platies | Hard water preference matches Val’s needs; fry hide in leaves |

| Tetras | Cardinal Tetra, Ember Tetra | Schooling looks stunning against green backdrop |

| Bottom Dwellers | Corydoras, Kuhli Loach | Root disturbance minimal; appreciate hiding spots |

| Shrimp | Cherry Shrimp, Ghost Shrimp | Graze biofilm on leaves; add cleanup |

| Snails | Mystery Snails | May nibble dying leaves (helps with melt cleanup) |

CHALLENGING COMBINATIONS:

- Goldfish: Will eat Val eventually, though it regrows faster than most plants they target

- African Cichlids: Compatible water parameters, but many species dig and uproot plants

- Large Plecos: May damage leaves accidentally; smaller plecos work better

- Silver Dollars/Buenos Aires Tetras: Notorious plant eaters, avoid completely

Val provides functional benefits beyond aesthetics. Those tall leaves offer surface cover for labyrinth fish like Bettas (reduces jumping), oxygen production throughout the water column, and nitrate absorption that helps maintain stable parameters between water changes.

Troubleshooting Common Vallisneria Problems

Let me share what I’ve actually encountered and how I solved it:

YELLOWING LEAVES

First thought: nutrient deficiency. But which one?

In Val specifically, yellowing usually indicates:

- Iron deficiency (new leaves yellow, veins stay green) → Add liquid fertilizer with iron or root tabs

- Nitrogen deficiency (older leaves yellow first) → Increase fish load or add nitrogen supplementation via EI dosing

- Calcium deficiency (stunted growth, pale leaves) → Increase water hardness

My 55-gallon showed persistent yellowing until I tested iron levels specifically. The standard API Master Test Kit doesn’t cover iron, I was supplementing potassium and nitrogen while ignoring the actual problem.

LEAVES TURNING BROWN AT TIPS

Usually not a nutrient issue. Check:

- Liquid carbon products like Excel (glutaraldehyde can damage Val at higher doses)

- Recent water parameter shifts

- Black beard algae infestation, brown tips can be early BBA

NOT SPREADING/NO RUNNERS

Val that stays solitary typically needs:

- Better root nutrition (add tabs)

- Time, healthy runners take 6-8 weeks minimum

- Adequate lighting (too dim = survival mode, no reproduction)

FLOATING UP CONSTANTLY

Root system not established. Plant deeper (bury 2-3″ of the crown base), use plant weights temporarily, or anchor with small stones until roots grip.

Invasive Species Warning

I shouldn’t end without mentioning this.

Vallisneria is classified as invasive in multiple regions, including parts of the United States and Australia. Once established in natural waterways, it out-competes native vegetation and alters ecosystem dynamics.

Never release aquarium plants into the wild. This includes dumping tank water that might contain plant fragments. Val can reproduce from small pieces, even a single runner section can establish a new population.

Check your local invasive species regulations before purchasing. Some states restrict Vallisneria sales or possession entirely.

When disposing of Val trimmings (and you’ll have plenty), dry them completely in the sun or bag them for garbage. Don’t compost aquatic plants near waterways.

Final Thoughts

Four years and probably 200+ individual Vallisneria plants later, I keep coming back to this species.

It’s not the prettiest aquarium plant. Not the most impressive to visitors who want to see red stems or intricate textures. But for reliable, low-maintenance, adaptable greenery that creates natural movement and provides genuine benefits for fish and water quality, I haven’t found a better option.

My beginner planted tank guides now include Val specifically because it rewards patience. That initial melt period teaches exactly the right lesson for new hobbyists: sometimes the best intervention is waiting. Not buying more products. Not changing parameters. Just trusting the process.

Start with one pot. Accept the melt. Watch the comeback.

You’ll understand why Victorian aquarists kept this plant 170 years ago, and why we’re still growing it today.